Bailing Out Hope

Posted Mon, 01/23/2012 - 6:32pm

by Bill Jungels

It’s the Friday before Christmas. As I approach the Gatehouse of the immigrant detention center in Batavia I am a little anxious about what lies ahead, but also amazed that what I thought was impossible last night is unfolding now.

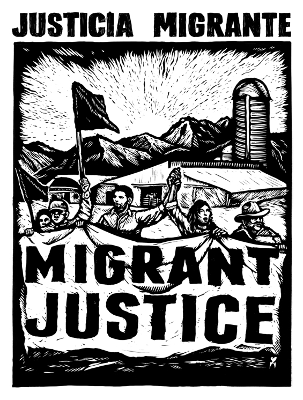

Since Christine Eber called me a week ago from Vermont I have been trying first to locate and then fruitlessly to get in to visit Eliasar Martínez, an undocumented farmworker and emerging leader who was arrested in Vermont. ICE quickly shipped him here, away from his network of support. But in the last 48 hours things have developed quickly. Brendan O’Neill, of Migrant Justice in Vermont, has gotten Eliasar’s correct “A Number” (One of the obstacles to my getting in to visit him). The Mexican consulate has intervened and gotten ICE to lower Eliasar’s bail from the punitive $20,000 to $5,000. And the Migrant Justice group has very quickly raised this amount, with a lot of the donations coming from other farmworkers like Eliasar. Why was the bail set so high? Along the border in Vermont and North East New York State, I.C.E. has a big budget and has special rules of enforcement and expedited procedures, and they set very high bails.

Then Brendan calls me at 5 PM yesterday and asks me to go bail Eliasar out today. My first internal reaction is “Not possible.” But Brendan is a very positive, committed guy. Those words won’t come out of my mouth.

Through a stroke of good fortune I have $5,000 in the bank withdrawn from our retirement funds to pay for work on the house. I never have more than a couple hundred in the bank, so this has to be fated, or, if you believe, Providence.

I haven’t met Eliasar yet but I feel like I know some things about him. In making my last documentary I interviewed a lot of young men being returned to Mexico by ICE at the border between Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora. I came to call that place the scrap yard of broken dreams. And I came to know well in Chiapas, Mexico, the young men who’d tried to cross or who wanted to cross or who’d crossed and come back. And to see the effects, negative and positive, on them and their families. I owe many of these indigenous campesinos from Chiapas a deep debt of gratitude for sharing their struggles through my documentary. Eliasar is from Chiapas.

That’s the poorest and most indigenous state in Mexico.

All week in addition to Christine and Brendan I have been receiving advice and encouragement from Carolina Kim of the Workers Rights Center of CNY (Syracuse) and Dr. John Ghertner who started a migrant support group in Sodus. Carolina advised me to call ahead to make sure the bail office would be open the Friday before Christmas and I found out that they are closing at noon. So I have hurried from the bank to get here in plenty of time. They take only money orders and bank checks.

I kind of run these things through my head along with some nervous anticipation as I walk from the parking lot to the entrance to the Detention Center. There I enter into a big lobby with an x-ray machine and a metal detector to pass through. The burly officer is cool but polite. He calls someone to tell them “We’ve got a bail case here”, and directs me to a sofa at one end of the big, mostly bare lobby. After 15 minutes or so a woman comes out to check and see if I have all the proper information and the right kind of payment. She’s polite and informative. She disappears again. She’ll be back and forth with varying stages of the paper work over the next hour or so.

Earlier I’d had a call from Martha Caswell of the group in Vermont. She is to serve as the contact person during this process. I have my phone with me and while I sit in the lobby, out of the blue I receive a call from Tom Potts who I thought was still doing free dentistry in Chenalhó, Chiapas. As we talk, the officer yells over and waves me to put away the phone. No calls permitted. Later I notice that I have a voice mail. To just listen can’t be wrong, right? Wrong. The incensed guard makes me take my phone out and leave it in the car. I comply sheepishly. Later I find that John Ghertner had warned me in an email that phones weren’t allowed. I’m not sure what the justification is. It fits in line with other things like the requirement that the “detainee” put you on a visitor list before you can visit them. They say they are protecting the prisoner’s rights. (There, I said it. They of course call them “detainees”)) But as in many other cases it seems that these privacy issues are being used by government agencies to protect their ability to do whatever they want to do and in this case to limit the prisoner’s ability to communicate with the outside world. Just as with the practice of transferring them to locations far from where they are known.

Eventually the woman appears with the finished paper work and I hand over the check. To my surprise I am told I must now leave the premises, including getting my car out of the parking lot. The process will take a couple hours, she says. Meanwhile, why not go get something to eat? On my way out I check at the guard house. They advise me to park on the road that runs by outside, “but on the far side, because this side of the road is still federal property.” It’s noon and I decide to take the advice and get something to eat.

Cruising Batavia’s main drag I spot a non-MacKingWendy family restaurant and go in. As I wait for my soup and burger I look around. The place is crowded with regulars. Families reunited for the holidays. All carrying on animatedly. I think of Eliasar. So far from his friends in Vermont. So very far from his family in Chiapas. Sitting in the jail with whatever companionship fate and shared hardship have thrown him. Chances are some of these people work there. It has to be a major local employer, because all afternoon I will be watching employees arriving and leaving past the gate house. Thus, especially in these hard times, communities turn to the burgeoning incarceration industry. Hell, the private prison industry wrote Arizona’s new draconian immigration laws.

I get back around 1 PM and park in the place the guards had indicated. I stare at the guardhouse. Perhaps behind the windows they stare back at me. I glance at a magazine I picked up at a drugstore in town. At 2:20 I spy a guard who has stepped outside to have a smoke, so I hop out of my car and approach within shouting distance. “Any news of Eliasar?” “They’re busy today. He won’t be released until 4 or 5 PM.” Back in my car I turn the engine on to run the heater from time to time. I have some extra sweaters I brought in case Eliasar has nothing for the cold. I put on an extra layer and go for walks, but never too far, because I don’t want to chance not being there if they release him.

Finally at about 4:30 a guard approaches the gatehouse with a young man. It has to be Eliasar. The guard indicates he can leave and I get out of the car and walk towards him. What can he be thinking about this grey haired stranger approaching him? Brendan has talked to him by phone and mentioned that a guy named Bill would be coming, but still he will have to put his trust in a stranger. He is a solidly built young man with strong high cheek bones and long dark hair that Christine told me he wears in a pony tail, but they have taken away his rubber band and so it falls straight down his shoulders. He carries of course only what was in his pockets when they picked him up and two books, One is a Missal. We shake hands with a little shoulder hug and get in the car. I’m trying to explain myself as I drive away as quickly possible. But before getting on the thruway I pull into a motel parking lot and call Martha and let Eliazar talk to someone he knows back in Vermont. Martha tells me they have already wired the money and it should be in my account by the middle of next week.

On the thruway I explain the plan to have him eat and spend the night at our house and to catch a bus back to Vermont early in the morning. He will live with a friend there. The original plan is for him to catch a bus to Plattsburg and get picked up there, but I emphasize to Martha that his trip would be a lot more secure If someone could be found to pick him up in Albany so that he didn’t have to deal with changing buses. Many of us have experienced how difficult it can be making connections in a foreign country where you don't know the language. And with us, usually someone can be found who knows English. Not so with foreign travelers in this country. And though his bail papers make him free to go about, he still might be approached and questioned by immigration officers.

On that trip home and at dinner and later that evening I learn some things about Eliazar. He is from the country, in the municipio of Las Margaritas, a section of Chiapas over towards the Lacondón jungle, very marginalized, very poor. His descent is from Mam indigenous peoples, but neither of his parents speak an indigenous language. They have a milpa, a small plot of land for raising corn and beans and other vegetables. They have enough only for auto-consumption, nothing left over to sell. I don’t ask him about his or their political or social affiliations. This is a dangerous topic in Chiapas and not something a stranger should inquire about. By his Missal though I guess that maybe he belongs to the Word of God movement in the Catholic Church. This is the progressive, social justice oriented strain of Catholicism in Chiapas, what we call “liberation theology”.

He has brothers who live in Tuxtla, the state capital, but he prefers life in the country. I had sensed a little uneasiness as we entered the urban area on the trip to Buffalo.

He tells me he worked for four years in Florida before coming to Vermont. I guess in agriculture and I wonder if he was involved with Immokalee, but no, he tells me he worked in a factory making computer cables. But he much prefers life in the country, and was pleased with the dairy work he was doing in Vermont.

Eliasar was followed by the migra in Vermont as Migrant Justive volunteer Jocellyn Reighley drove him to a dental appointment. On the way home Immigration stopped the car “because it had Florida license plates, and it was their job to investigate suspicious activity like that.” There is a wonderful video about this at http://migrantjustice.net/node/133.

It has lots of images of Eliasar.

At home I ask Eliasar what he’d like to eat and rattle off a few possibilities. He chooses Chinese, so I suggest a trip to the Co-op to buy veggies. He looks at me with concern. Está bién? Is it Okay? After living in fear of going anywhere for so long he is now in the paradoxical situation of temporary freedom bracketed by long term lack of freedom. With his bail papers he is free to move about, but on call for hearings and an eventual decision that will almost surely result in his deportation. So off we go to the co-op and buy snow peas and other things to stir fry.

During dinner I receive the welcome message that Aaron Lackowski from the group in Vermont has volunteered to drive 4 hours each way to Albany to meet Eliasar on the Saturday of the holiday weekend. There are lots of good people working for the migrants in Vermont.

One of the things Eliasar had with him when he was arrested was his cell phone and they have given it back, but of course he doesn’t have his charger. He is quite concerned about having his cell phone to use on the trip and I can understand why. It is his lifeline. It is his only connection, in a strange world of people who don’t understand his language or have any concern for his welfare, with those who do. So after dinner our first stop is at Radio Shack where we get a charger that fits.

Then we are off to the bus station where we get his ticket. I figure if we do that now we won’t have to arrive early in the morning and it may save him some hassle and explaining with the migra who always patrol the bus station. This turns out to be a very bad mistake. When we arrive in the morning the bus to Boston is already full. With the holiday, Greyhound has way overbooked and there are 15 people wondering what is going to happen to them. Eliasar waits inside the terminal while I run around trying to find out if another bus will be brought in. Eliasar is confused and concerned. In Mexico the big bus lines have reserved seats and I’ve never been on one that was overbooked. Not getting any information I go out and stand by the closed bus door. The driver arrives back from whatever report he has been making and asks me if I have a single ticket. I say my friend has and run back into the terminal to get Eliasar. By now several other people have caught on and the driver is letting them on presumably to occupy the aisle for the first part of the trip. I fear his largess will run out but I urge Eliasar to thrust his ticket at him and he takes it. We have time for only a quick handshake hug and then I wait until the bus pulls out. I feel a great sense of relief. Now he will get off the bus when Aaron is there to meet him in Albany.

On New Years day Eliasar has the kindness to call me and wish me a Happy New Year and thank me.

I thank him and all the immigrants who work so hard to put food on our tables and help us in a hundred other ways and receive so little in return. But it is enough, as I have seen in many cases, to live a life of hard work and dignity when they return to Mexico. And in Eliasar’s case I am sure it will be a life of service as well.

And even more, I thank him and his family and all my indigenous friends in Highland Chiapas for preserving through hundreds of years of resistance a way of life that is counter to our globalized lives, corrupted by consumerism and corporate slavery. Their way of life is threatened as never before, but many I know are resisting with strength. Gary Snyder said you can only judge civilization by holding it up to the standard of wilderness. Likewise, you can only judge our urban culture by comparing it to indigenous and campesino cultures, and I say this without any romantic illusions about the latter, They hold out for me, even at my age, the hope for change.