"Driving for Justice: Volunteering with Central American workers on Vermont dairy farms" by VTMFSP Volunteer Solidarity Driver Christine Eber

Posted Tue, 09/06/2011 - 10:21am

Cars whiz by as I slow down to make my exit off the interstate north of Burlington, Vermont, not far from the Canadian border. I’m on my way to a dairy farm where I’ll pick up a couple young men from Guatemala and Chiapas, Mexico.

My google map directions take me through a patchwork quilt of green hills dotted with red and white barns and houses with freshly mown yards. Where I come from in rural New Mexico yards are often home to assorted broken-down cars, trucks and farm equipment. Life’s messiness and decay are there for all to see. In Vermont disorder and breakdown are not so much in the things along the roadside, but in the ties that bind people from drastically different worlds in a struggle to support their families.

I’m driving slowly in order not to miss my turns and to keep my eye out for the border patrol. Their daily presence on the roads keeps Central American workers on the farms and volunteer drivers like me careful not to do anything to call their attention. I’m a new volunteer with the Vermont Migrant Farmworkers Solidarity Project (VTMFSP) based in Burlington. I transport farm workers to organizing meetings throughout the state. I am grateful for this opportunity to support their efforts to come together to find ways to ameliorate the unjust conditions of living as undocumented immigrants in rural Vermont.

I know something about why they have come this far from my experiences as an anthropologist in Chiapas. When I tell people about the deepening poverty in Chiapas and how people must leave their homes to find work in the U.S., I’m often asked: But there must be some jobs in Mexico! Yes, I say, there are, for short periods of time, often under demeaning and abusive conditions, at a long distance from home, and for as little as $5.00 a day. If you were making that little and a relative told you there was work on a dairy farm making $8 an hour, might you not go, too? Still, it takes courage to leave one’s home, cross the U.S./Mexico border, and then traverse nearly the whole United States to arrive in Vermont. Only the dream of earning enough to help their families live better lives keeps these men and women moving, and then working, day after long day.

I take my last right turn to the farm where I’m to pick up Elias and Vicente (not their real names). Stepping out of the car I am taken aback by the odor of a dairy farm. I imagine that this smell is not at all offensive to the farmers and their workers and wish that I were accustomed to it, so I wouldn’t seem as if I wanted to get back in the car as soon as I could.

Elias and Vicente live in an apartment at the end of the barn. Vicente greets me as I enter the barn and asks me if I can wait a few minutes for them to get ready. While he disappears into the apartment, I greet another worker who I presume will take the milking shift while Vicente and Elias are at the meeting. This dairy farm is one of Vermont’s many small farms, with only three Central American workers, in addition to the family who owns the farm. Milking goes on around the clock . Workers typically have one day off a week, but sometimes they work every day.

Soon the men and I are in the car and on our way to the community center in a nearby village where the meeting will take place. Workers are coming from this part of the state to get together for their fourth meeting. This is Elias’ first meeting and he is eager to learn what it is about. I don’t know much myself, but I tell him how good it is that he is participating, even if just to talk with others in a similar situation.

We arrive early and help Natalia Fajardo and Brendan O’Neill, VTMFSP staff members set up the chairs and lay out plates of tacos, pizza, rice, beans, and tortillas. Once the twenty or so farmworkers have arrived and begin to introduce themselves, we volunteers leave for a couple hours before returning to pick up our passengers. Today I stay around as I’m needed to help Sebastian, one of the farm workers who is a single father with an eight year old son, Pedro. While Sebastian meets with the others, Pedro and I take a walk around the village, examine the vegetables in the community garden, and play board games.

Pedro hasn’t been in the state long and he is excited to start 3rd grade next week. I am relieved to learn that Pedro lives on a small farm where Sebastian is the only worker in addition to the farmer’s family. The farmer and his family treat Pedro like one of the family. Pedro swims in their pool and plays with their own and the neighbor children. He also enjoys helping his dad with his work.

After the meeting I talk to Sebastian’s employer, a farmer whose family has been in the dairy business in Vermont for a few generations. Like other dairy farmers in the state, this man is struggling to keep his business going. In the 1950s Vermont was home to 11,000 diary farms. Today, as a result of economic liberalization polices, not unlike those threatening small Mexican farmers, Vermont dairy farms number around 1,000. Government policies favoring transnational diary businesses and price fixing by dairy monopolies are only two of the many impediments that small farmers face to make a profit on milk.

I am impressed that Sebastian’s employer is concerned about his rights and the general welfare of workers on diary farms. “It’s important for these men to get to know others like them, “ the farmer tells me. I am learning that many dairy farmers share his commitment to creating more just conditions for farm workers in Vermont, while at the same time trying to keep their businesses economically viable.

At the meeting’s end the attendees seem reluctant to leave. They share cell phone numbers and say long goodbyes. On our way home another man joins us in the car. Reymundo’s employer took him to the meeting but couldn’t pick him up. Reymundo has only been in Vermont a couple weeks and as I drive him back to the farm he has little idea where he is in the vast expanse of rolling green hills and fields and houses and barns that all look much the same. Fortunately, my google directions get us to the dirt road that winds up a hill to his farm, which seems quite remote from other farms. As we approach the farm the three men talk about living far from one another and in isolated conditions. In the rear view window I catch a glimpse of Reymundo’s face, his guardedness gone for the moment. “Here we’re like chickens in a coop,” he says, eyes fixed on the clouds moving in.

After dropping off Reymundo we make our way back to the farm where Elias and Vicente live. On the way I learn that the last time that Elias left the farm was five weeks ago to attend an event at Goddard College where the Mexican consulate issued passports for a nominal fee. A Mexican passport is a great help to Elias and other undocumented workers, most of whom have no driver’s license or other identification. A passport will enable Elias to return to Mexico by plane, avoiding the possibility of being detained and eventually deported by immigration officials on the U.S. side of the border, or of falling into the hands of corrupt police or drug traffickers on the Mexican side.

Elias tells me that they rarely leave the farm for fear of being detained by police or immigration authorities. Their employers go to the stores for them or transport them to and from stores on occasion. This is also the case with another group of workers that I transported to the Goddard College event. Hungry after the long day, the men asked my fellow driver and me if we could stop for hamburgers. They had in mind going through McDonald’s drive-thru because they were afraid to get out of the car. When we couldn’t find a McDonald’s we finally convinced the men that they would be safe at Al’s French Fries, a popular restaurant in Burlington. As we munched on hamburgers and fries surrounded by children and their parents enjoying the Saturday afternoon, the border patrol seemed a distant threat.

Each time I walk on the streets of Burlington or drive to see my grandchildren in the country nearby, I think about the injustice and irony of being unable to move freely in the “land of the free.” Walking or driving on the streets or roads of Vermont, undocumented workers stand out from the predominately white population. Walking and driving “while brown” can lead to arrest, detention and deportation. So, to keep their jobs they stay on the farm.

In my encounters with farm workers and their families in Vermont I am struck by the potential and broader humanity of these people and how it is being constrained by abusive immigration policies. Most of the farmworkers are limited to a few identities, that of workers and co-workers. Those who are living with brothers, sisters, spouses or other relatives also have the opportunity to enjoy bonds of kinship. But the majority of the workers - young , single men and a few women – have no way to become a boyfriend, girlfriend or spouse while they are living in isolation on Vermont farms. They can only dream of one day returning to their homes in Central America where they hope to find someone to love and start a family with. Those workers whose children and spouses are back home suffer greatly, unable to accompany their children as they grow, to feel the comfort and joy of hugs and kisses.

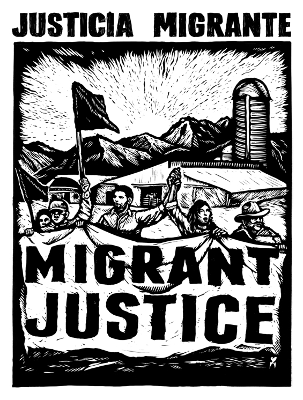

With the support of the Vermont Migrant Farmworker Solidarity Project workers are now taking on new identities as organizers. These men and women are learning skills that will hold them in good stead when they return to their home countries. These new identities were on display recently at an historic press conference organized by the VTMFSP at the state house in Montpelier on August 18, 2011, the first time migrant workers in Vermont brought their concerns as a community before an elected official. Danilo López and Ober López, from Chiapas, read a letter that they and seventy other farmworkers signed addressed to dairy farmers throughout the state to enlist their support to oppose the Secure Communities program, a government initiative that would make local police arms of ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). The letter states: “Such programs also affect you as an employer because when we run the risk of arrest, it leaves you without workers and damages your farms and threatens your income. In order to recruit new people you must again teach them the operations of the farm, only to run the risk of repeating this history over again.”

In his remarks Danilo stated, “It is not fair for migrants to be treated as criminals. If it is a crime to not let a family member starve, then, logically, we are all criminals, since one would do anything for a loved one. If the situation were the opposite, if Americans had to migrate to give their families a better life, would they like to be treated with racism? Our skins are different, but our hearts are the same.”

I also became more aware of the potential of returned migrants to confront abuses in their home countries when I was last in Chiapas and spoke with María Elena Fernández Galán, a librarian with the Institute for Indigenous Studies in San Cristóbal de Las Casas. María Elena has spoken with many migrants who have returned to Chiapas after working in the U.S. She is impressed by their knowledge of their rights and their resolve not to be treated disrespectfully wherever they live. I am encouraged by this outcome of working in the U.S. and hope that when migrants with organizing talents like Danilo and Ober return home they may find a way to use their skills and awareness to work with others to demand changes in the exploitative and racist labor systems in their home countries as well as throughout the Americas.

In a speech on January 8, 2008, in the wake of marches throughout the nation demanding humane immigration policies, President Obama stated: “We aren’t going to deport 11 to 12 million people. Many have been here for a long time. Many have strong roots. Some have children who were born here, therefore making them United States Citizens. It is hard to imagine that we want to live in a country where we would have police and immigration officials coming into people’s homes and taking away the father of a family, sending him back to Mexico leaving a mother and children behind. This is going to be an emotional issue. It’s not going to go away any time soon. But I think that what we saw in these marches is the face of a new America. America is changing and we can’t be threatened by it.”

Despite Obama’s promise, during his administration a million heads of households and whole families have been deported. If made mandatory, the Secure Communities Program would lead to mass deportations of millions more immigrants. Sadly, many Americans seem to have no problem living in a country that deports hardworking people, tears apart families, and weakens whole sectors of our economy, such as the dairy industry in Vermont. I want to believe that if these people were to meet the workers and dairy farmers who I have met, they would be compelled to think hard about the kind of nation we have become and work with others to make it more democratic. May we all speak out for justice and may our elected leaders listen to us and find the courage to stand up for our nation’s founding principles, the right of all people wherever they live to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

For more information or to get involved with the Vermont Migrant Farmworker Solidarity Project:

www.migrantjustice.net

vtmfsp@gmail.com

802-658-6770